Blog

AI in Art & Creativity

By D.Moreno

Tags: Opinion, Art, Artificial Intelligence, Art History

Why concerns about these new tools are echoes from previous generations and what they mean for the future of art and creativity.

📌 TL;DR

Art and creativity have historically benefited from advances in technology.

Advances in the tooling available for creative expression have invited a reevaluation of each medium’s place in the art world, and invite some reassessment of whether art made with the new tooling is ‘high art’.

AI art will no more undermine the value of artists in our future than cameras have to paintings since their introduction in the 19th century.

| Art evolves in response to changing tooling |

|

| Changes in art technology come with a democratization of… |

|

| There is a history of debate around whether machines can be creative |

|

📕 Book Recommendations

- Life3.0 by Max Tegmark

- for more on where we draw the line for human level AI, why it may have shifted over time, and how human level AI might develop in the future.

- The Age of AI by Eric Schmidt, Henry A. Kissinger, Daniel Huttenlocher

- for more on what it means to be human in a world shaped by AI.

AI Wins Art Contest, Community Pushes Back

I feel like, right now, the art community is heading into an existential crisis if it’s not already. A big factor of that is … the disruptive technology of open AI. A lot of people are saying, ‘AI is never going to take over creative jobs, that’s never going to be something that artists and sculptors have to worry about.’ And here we are smack in the middle of it, dealing with it right now.

— Jason Allen, Colorado State Art Contest Winner

Allen's First Place Entry in the Colorado State Art Contest

This past September, Jason Allen entered a piece of digital art into the Colorado State Art Contest and won first place. Jason Allen revealed in a discord channel afterwards that he had used Midjourney, a text to image AI system, much to the dismay of others in the Midjourney discord community and many other folks online.

This sparked debate about whether Allen had cheated the contest by entering a work that wasn’t created by himself 1. This also opened up debates about whether AI generated works are art, and what place the tool has in the creative process moving forward. There have since been a number of communities that outright prohibit entries that were generated using AI and trending movements to promote banning AI art. Some in the art community have taken a more aggressive position, calling into question intriguing concerns around licensure of AI generated works on the basis that an AI creates based on information extracted from data in its training dataset. Of particular interest on the issues around licensing are prompts that solicit content from AI that is in the style of known artists or that mimic copyrighted material.

New Tech, Same Tensions

Art and creativity have evolved alongside advances in technology. Some artistic movements were enabled by advances in the tooling and technology available to artists, and in other cases radical innovations in the tooling available to generate imagery have transformed prior mediums’ place in the artistic world.

At each epoch of our creative tooling, there are concerns that the artistic vanguard are a threat to tradition and technique.

Art continues to thrive, and some in these communities celebrate the release of new mediums as emerging methods for creative expression. As the accessibility of technology spreads through civilization we see that the new methods of creation carry a democratizing force: more people are able to participate in the art making and art ownership.

Technology and Art

Advances in technology and movements in art are inextricably linked. As a result, the boundaries of what we consider creativity and art are also sensitive to the evolution of the technologies that enable their expression. Technological advances, from premixed paints to the proliferation of microprocessors, have democratized the creative process. Participants in traditional mediums and critics have resisted movements enabled by radical changes in artistic tooling and consequently invited a reevaluation of the line that separates creative expression from expressionless content.

Tube Paint Wielding Impressionists

The romantic wave, which was ushered in with the 18th century literary movement, led to an era of imagery that focused on photorealistic imagery capturing a certain ideal, washed in tones that heightened their beauty and allure. Nonetheless, the images were praised for their minutiae, which highlighted those artists’ technique and mastery of the depiction of our physical world, observed through our emotions. This movement was characterized by an imaginative finish to visual art that invited observers to connect deeply with the emotions captured in the imagery.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, artists in France popularized impressionist painting which favored the capture of raw, authentic imagery in lieu of fabricated scenes that had dominated the art world. Characteristic of this movement were the sketch-like, seemingly unfinished, paintings of unstaged scenes. Artists of this time explored painting ‘Plein Air’, opting to bring their creative process to the world around them as opposed to imagining contrived imagery from the comfort of their studios. The movement marked a shift from projecting idealism in imagery towards capturing the idiosyncratic happenings of real life: no longer were these artists comforted by controlled lighting, controlled setting, and controlled weather. By leaving these comforts, the Impressionist captured a particular moment faithfully albeit unrealistically.

The impressionist movement was enabled by technology.

In the mid-19th century commercial availability of portable art easels and an American oil painter John Goffe Rand’s invention: the portable syringe of premixed paint, enabled artists to bring their painting to the outdoor world 2. Artists began capturing minimalistic paintings of unstaged scenery, which also popularized landscape impressionist painting. Previously, outdoor painting was relegated to sketching while the true polish and expression of technique came in the studio. This was a necessity for any imagery that required a diverse palette because artists needed to meticulously mix dry pigment powders with organic oils to make the hues they sought to use in their works.

There was resistance to this change.

Critics, along with the masters of Romantic idealism, dismissed early Impressionists and their works. The critique focused on the works appearing unfinished. The era’s namesake itself was an appropriation of Louis Leroy’s critique of a work by the now globally renowned Claude Monet: Impression, Sunrise 3.

Claude Monet's Impression, soleil levant

Published in Portfolio magazine, Art Foundation Press

Photography: An Art & Science

Concurrent with the developing tensions between Impressionists and Romantics was the emergence and use of photography. This new medium emerged as a scientific tool where it was adopted in fields like botany and archaeology for its ability to faithfully capture the physical world in great detail 4.

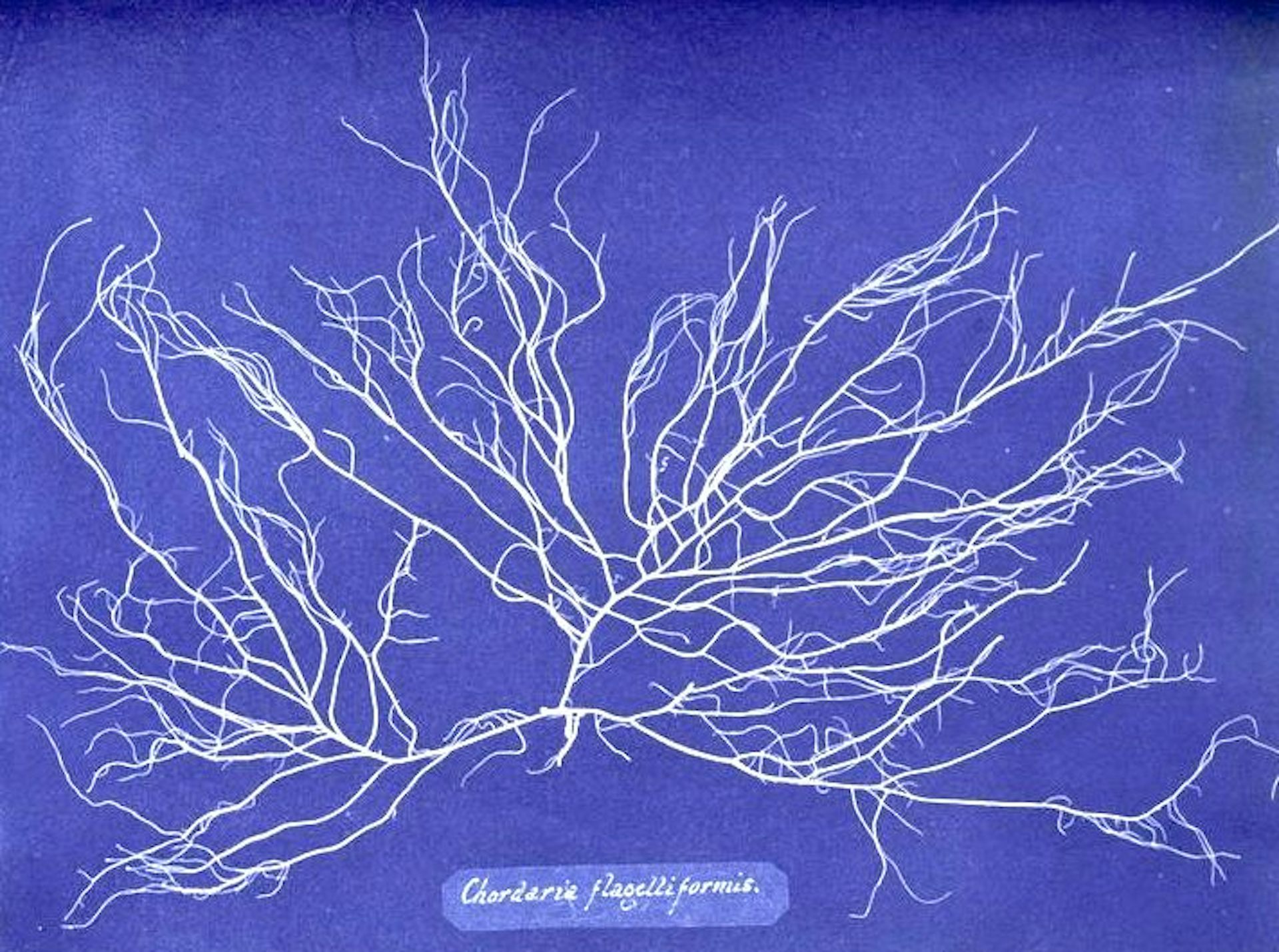

Early photography used in physical sciences

Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions (1843)

This technology was adopted into broader use and it was received by an enthusiastic public that quickly took to the method of capturing subject matter with a level of accuracy that was otherwise unimaginable without years of formal training and practice. The early-adopting artists found the monochromatic medium a challenge: photographers grappled with obstacles like capturing texture and tone in grayscale. They also paved the way for the medium’s further adoption through experimentation and cataloging methods for capturing imagery and developing the photosensitive substrate. Pioneering photographers of these early days were squarely at the intersection of art and science.

There was resistance to this change.

Photography was a technological advance that fundamentally changed the availability and accessibility of tooling used to generate imagery. Previously, painters would be often tasked with capturing spaces, people, and time in imagery. A wealthy family wanting a family portrait contracted a skilled painter whose work would both capture and flatter their image. In these times such a portrait would become a mark of the family’s wealth, and be passed through generations as heirloom. In this context: photography replaced canvas with photoreactive metal sheets, the brush with a shutter, and the painter with a photographer.

Critics of photography were plentiful. A photograph is unforgiving where the portrait painter would flatter their clients. Details painstakingly added to a landscape, demonstrating years of a technique’s mastery, were replicated with equivalent or higher detail by harnessing chemical properties and mechanical manipulation of light. The resistance came from: the traditional medium artists, art collectors, and art critics. For the artists the sentiment was that this new medium posed an existential threat to the craft. The critics gravitated towards photography’s process: the claim being that the medium lacked depth and spirit because the capture was mechanical and manufactured 5

Photography & Impressionism Intersect

The collision of these mediums did not result in the slow fizzling-out of the old. Instead, the intersection of these technological and artistic advances invited a reimagination of each medium’s place in the world moving forward.

The introduction of a low barrier-to-use photorealistic medium resulted in a market flooded with precision manufactured imagery. It is argued that overtime this drove a trend towards abstraction in painting 6. This does not mean that photorealistic painting vanished; on the contrary, there continued to be a market for photorealism despite the introduction of a faster, cheaper, more accessible medium to capture reality.

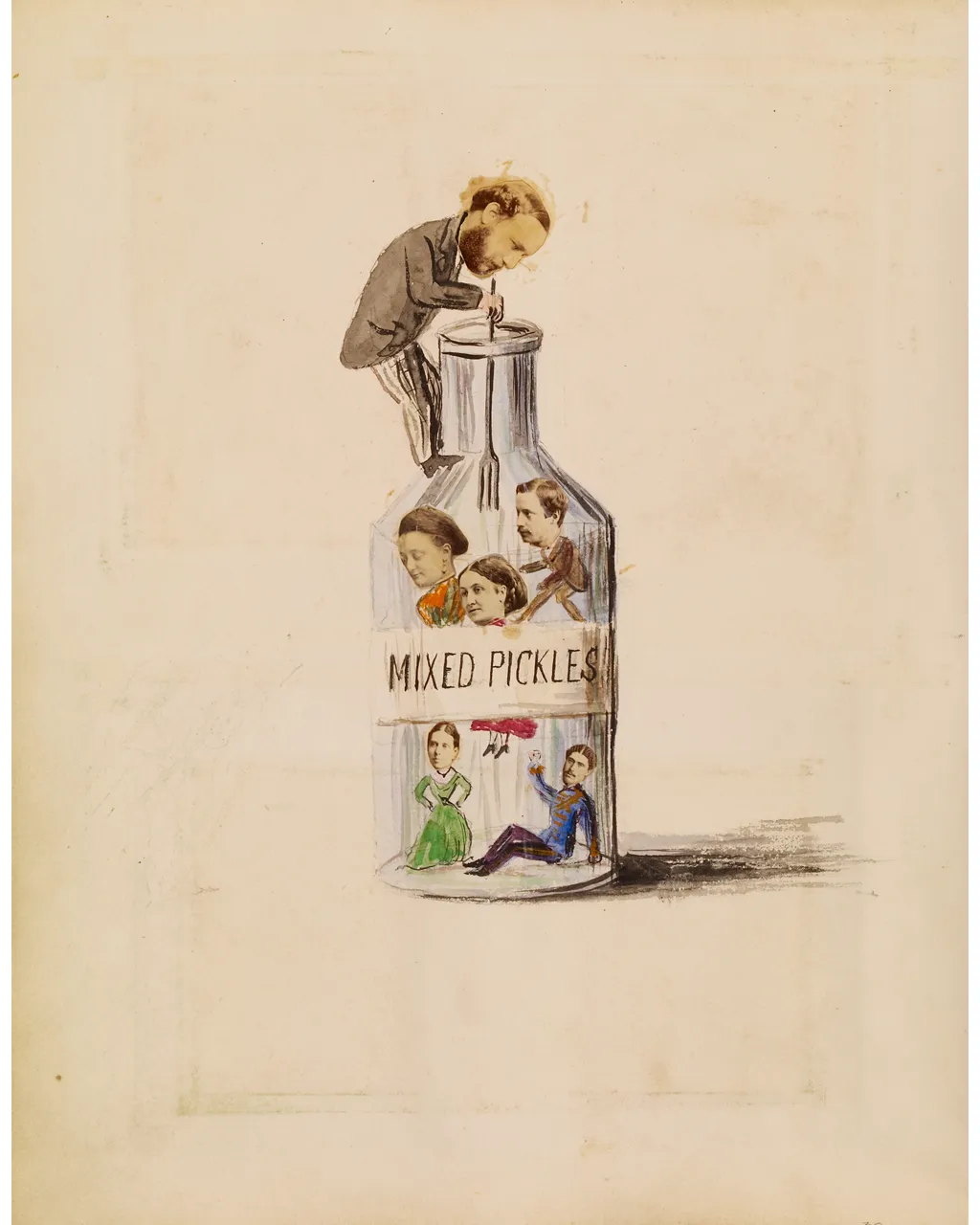

Photography also evolved and its movements invited repeated debate as to its merit as an artform. It is generally accepted today that photography is an artform, though there are still some that argue about it. Movements in early photography included editing images into photo-collages that came in a spectrum from the pursuit for beauty all the way to absurdity:

Mixed Pickles, by Victoria Alexandrina Anderson-Pelham and Eva Macdonald

Westmorland Album, circa 1870

By Marie-Blanche-Hennelle Fournier

Collage of watercolor, ink, and albumen silver prints

Others took to editing the negatives of the images: selectively controlling exposure, layering negatives, and fine-tuning focus to create blurred prints. These effects turned photography into a craft, indeed a parallel to the craft of painting.

The Flatiron by Edward Steichen

Printed 1904, ref: Met Museum

Overtime photography introduced a new medium for creatives to explore, and as more explored it the adoption lent itself to the merit of the medium as an art form.

AI in Art

There was a fear at the time of its introduction that photography might supplant painting as the technology improved 5. That may not have been realized, but the trajectory of painting as a medium was irrevocably impacted by the radical change in the tooling available to generate imagery that was brought on by the introduction of photography. Similar fears have arisen recently aimed at generative machine learning models: that take in text prompts and generate images.

While this new application of AI has also changed the availability of image-creation tooling; the use of AI in art is not new.

Tooling available for photo and video editing has made use of machine learning models for much of their modern existence: single click background blurring, video editor object tracking, and redeye correction, these operations invoke image recognition software. More sophisticated editing software may propose likely edits intelligently based on the content of the image: edits including contrast, tone, image sharpening, filtering etc. The content recognition and proposed edits are the result of applied machine learning.

Technology in Art: A Democratizing Force

Art has evolved in reaction to, or enabled by, technological changes in the tooling available to the artists. Furthermore, at each age in the tooling environment the new comes with a democratizing force that enables more people to participate in the art making and more people to participate in ownership of art.

Before the camera, only a select few would ever learn, or perhaps ever have the innate talent to, produce photorealistic painting. Photography made more accessible the tooling that could be used to produce such images. It also made having a family portrait no longer a mark of the elite class.

The invention of tube premixed paints launched a series of innovations: over time improved tube designs as well as the introduction of synthetic paints meant more variety, increased availability, and lower prices. Today, for roughly the price of a dinner out anyone can get started with an art easel, paint set, and some sketchpads.

AI in art is also a democratizing force. It is now possible that anyone with at least internet access on a device with a screen is able to generate images in the style of any artist, of any era, of (almost) any subject matter. Just don’t ask it to draw hands :ok_hand:

AI Rendering of Michelangelo-like Painting

Stable Diffusion, prompt: ‘Painting on a cathedral roof in the style of Michelangelo’

Technology and Creativity

The effect of technology on creativity is less clear. On one hand: we can say that new tooling has created new methods for creative expression. On the other: it seems that over time, and with more sophisticated technology, more of the creative process has been delegated to machines.

For instance, a craft perfected in dark rooms to edit negatives and create prints has been increasingly automated in digital creative studios. We’ve reached a point where our machine counter-parts will go as far as selecting the best of a series of burst photographs taken on your device, and then suggest the optimal edits for that image selected from the burst. All of this happens automatically, and the technology exists in your pocket. It would seem that just about the only thing we have not delegated to machines is deciding what to photograph.

Today, the technology exists to generate photograph-like images of just about any scene, all from a text prompt. With generative ML we are left tussling with whether or not this AI is capable of being creative and what that means for the future of human artists. This encroaches on a philosophical debate rooted in the ambiguous definition of what is creativity, though exploring this debate will be left as an exercise for any motivated reader so inclined to dive in… I will; however, leave this out of the scope of this post.

An Early Creative Robot

In the early 70’s a British born artist named Harold Cohen engineered a robotic system that generated imagery algorithmically. AARON, as the collection of algorithms and engineering projects came to be called, is ‘one of the longest running and continuously maintained AI systems in history’ 7.

Harold Cohen & AARON

Harold painting over a sketch produced by his creation AARON

Harold applied color to the sketches the machine created. In doing so he created a man-machine artistic relationship. By the early 80’s the man-machine duo were making their mark in the art world by sharing their works in exhibitions and museums. Harold claimed that AARON was a system embedded with his own knowledge and that AARON was therefore not a creative machine but rather a tool available to Harold in his art making. Indeed, all but a few of the cocreated artworks were signed by the artist: Harold Cohen.

“I think creativity is a relative term… Clearly the machine is being creative, the program is being creative, to the degree that every time it does a drawing it does a drawing that nobody’s ever seen before including me. I don’t think it’s currently as creative as I am in writing the program, I think for a program to be fully creative, in a more complete sense creative, it has to be able to modify its own performance and that’s a very difficult problem”

— Harold Cohen

Harold Cohen, 'Another Spring'

Oil over pigment ink on canvas, triptych. 2011

As AARON and Cohen made their mark on the art world, their works invited great debate around the topic of whether AARON was / could be creative. As AARON’s feature set grew: first from sketching lines then to filling in its own works with color, the debate in favor of it being a creative machine gained some support.

Can AI ever be Creative?

A vision for artificial intelligence of yesteryear may have imagined a world with autonomous vehicles and HAL 9000 like sentient infrastructure. While today we would hardly consider a self-driving vehicle a human-equivalent artificial intelligence, despite its ability to solve for safe maneuvering in a risky real-time analog environment. Overtime we push our threshold for true artificial intelligence seemingly as soon as our systems have breached the previous definition, or maybe as soon as we become desensitized to the achievements of the current gen tech.

The boundary of what we consider true, human equivalent, AI has been periodically reevaluated.

Either way: creativity, like human equivalent intelligence, seems to continually evade the reach of AIs. This could arguably be left to the fact that the criteria is somewhat nebulous, but it could also have some rooting in our collective resistance to attribute something we feel separates us from machines (and, perhaps, from other species) to objects of our own creation.

And Will AI-Image Generation Always be Derivative?

A common argument, in fact one that has raised interesting legal questions regarding licensure, is the question of whether image generating ML is derivative (and how derivative it is) in relation to the training data that was used to create the model.

These questions are intriguing, and beyond the scope of this post - though important.

If we would say that a system is derivative if its execution falls within the bounds of observed or encoded behavior, then it it important to acknowledge also that image generation may only be derivative for now.

In 1997, DeepBlue beat the world chess champion by executing expert chess strategies codified and run on purpose built and optimized architecture. We might say DeepBlue was derivative because it took human expert knowledge and applied it using overwhelming compute power.

In 2015, an artificial neural network developed by DeepMind Technologies called AlphaGo beat a world-class, professional Go player. This algorithm by the same metric was partially derivative: the algorithm was seeded with human Go games and human expert Go player strategies, and then used reinforcement learning to fine tune itself by playing additional games against itself.

Today, the world’s best Go player is AlphaGo Zero. A neural network also developed by the same lab. The key difference here is that by the same metric this intelligence is not derivative. AlphaGo Zero was not seeded with human games and human strategies; instead it was trained entirely by playing games with itself. Like many first timers, it played Go terribly. In the first 3 days of its existence, AlphaGo Zero played almost 5 million games against itself. A few days later it achieved a proficiency that was comparable to global elite players 8.

Systems like AlphaGo Zero require human researchers and engineers to define the rules and the boundaries of the sandbox, then the ML model is tasked to optimize for some objective function. Translating the creative process and purpose to codified rules and a sandbox may prove a challenge, but it is within the realm of possibility that an image generating AI may someday be non-derivative. If that day comes, the question of whether machines can be creative will come to term and our collective hand will be forced to make a decision.

The future of AI in Art & Creativity

Art has evolved in reaction to shifts in the content creation tooling environment. This has necessarily invited a reevaluation of existing mediums’ strengths as the new tooling made cheaper, faster, more accurate, or some other dimension of content generation better than anyone could have previously imagined.

Machine use has been shifted further left in the creative process during each advance. More of our creative processes are either enabled by or completely delegated to machines (e.g. picking the best picture from my burst, editing it, etc). Delegating more of the creative process to machines has allowed us to focus our attention on other, more intriguing matters (e.g. what is worthy of photographing).

There was a time when Socrates warned his pupils of the perils of writing; or rather, relying on the written word. In those times sharing knowledge was an oral exercise, and Socrates warned that relying on written text might make scholars’ minds lazy and forgetful. Of course this is draped in a rich irony: we only know of Socrates’s stance on written word through Plato’s writings that have survived many generations and translations. The availability of scribes and a consolidation of the Greek alphabet preserved Socrates’s thoughts at that time. Written word is to the academic tradition what these large-shifts in content creation tooling have been to art. The reliance on written word, and many other advances in technology, no more undermined scholarly pursuit than photography did to painting.

It’s important to frame our current concerns with ML generated art within the lens of our own history: the introduction of photography didn’t bring an end to painting, phonographs didn’t kill live performances, computers have become the best Go and Chess players on the planet yet these past-times are still enjoyed by many people globally.

Finally, and maybe most importantly, each seismic shift in our creative tooling environment ushers in a greater accessibility to the creative process. As a result, more people are able to participate in the art making and art ownership.

-

Mattei, Shanti Escalante-De. “Ai-Generated Artwork Goes Viral after Winning Award at State Fair.” 1 Sept. 2022, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/colorado-state-fair-ai-generated-artwork-controversy-1234638022. ↩︎

-

“En Plein Air - Modern Art Terms and Concepts.” The Art Story, https://www.theartstory.org/definition/en-plein-air. ↩︎

-

Samu, Margaret. “Impressionism: Art and Modernity.” Metmuseum.org, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, Oct. 2004, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/imml/hd_imml.htm. ↩︎

-

Locke, Nancy. “How Photography Evolved from Science to Art.” The Conversation, 25 Dec. 2022, https://theconversation.com/how-photography-evolved-from-science-to-art-37146 ↩︎

-

Teicher, Jordan G. “When Photography Wasn’t Art.” JSTOR Daily, 6 Feb. 2016, https://daily.jstor.org/when-photography-was-not-art. ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Silva, Eva. “How Photography Pioneered a New Understanding of Art.” TheCollector, 24 June 2022, https://www.thecollector.com/how-photography-transformed-art. ↩︎

-

Garcia, Chris. “Harold Cohen and Aaron-a 40-Year Collaboration.” Computer History Museum, 23 Aug. 2016, https://computerhistory.org/blog/harold-cohen-and-aaron-a-40-year-collaboration/. ↩︎

-

Knapton, Sarah. “AlphaGo Zero: Google Deepmind Supercomputer Learns 3,000 Years of Human Knowledge in 40 Days.” The Telegraph, Telegraph Media Group, 18 Oct. 2017, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/science/2017/10/18/alphago-zero-google-deepmind-supercomputer-learns-3000-years/. ↩︎